AS I PULLED UP to Braleys Way Landing on Edgartown’s Eel Pond in pitch black darkness at 4:30 AM on Sept. 22nd, I did not like what my headlights revealed. The wind, which had blown like stink out of the northeast the day before, had indeed shifted due north as predicted– but had by no means abated to the forecast 5-8 knots; whitecaps signified a steady 15 knots at least. That meant that the seas outside the Pond’s protective barrier beach would be choppy, steep and occasionally breaking; a far cry from the calm conditions we’d been hoping for… but at least the air was warm. After hurling a stream of colorful invectives to the weather gods, I turned on my miner’s headlamp and began unstrapping the kayak from the roof of my car– very carefully, as my new 18’ boat, at a featherweight 28 pounds, could easily blow off its cradle given a moment’s inattention.

Dana, Tucker, John Ready to Go!

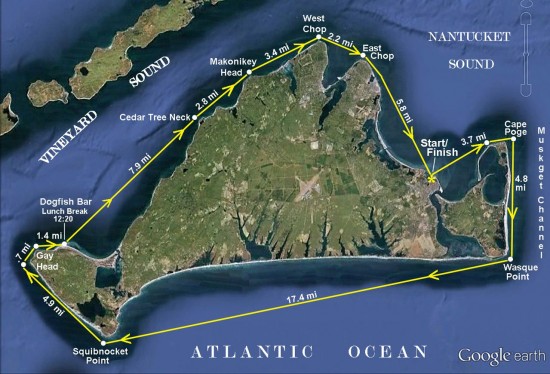

Setting the boat in the marsh grass at pond’s edge, I went through my checklist and brought down the rest of my gear: paddle, PFD , one drybag with cell phone and first aid kit, another with extra clothes and towel, two Camelbak hydration packs (one with 80 ounces of water, the other with an equal amount of GatorAde), and a soft-sided cooler with lunch and snacks. In the pockets of my PFD were a VHF radio, assorted Powerbars, Powergels, and a banana; around my neck hung sunglasses and a waterproof digital camera. Lastly, I affixed the Garmin GPS to its foredeck mount; this magical device would provide continuous feedback on how fast we were going, how far we’d paddled, the distance to our next objective, and how long it would take us to get there. Over four lengthy outings earlier in the summer, I’d assembled a course of twelve “waypoints” which, if followed successfully, would take us all the way around Martha’s Vineyard– a distance of 55 miles– in a single day.

Headlights signaled the arrival of my paddling partners, John Karoff of Milton and Tucker Lindquist of Ipswich. We knew each other as veterans of the New England open water racing circuit; John’s cousin owns a house in Lamberts Cove, so he’d also spent a fair amount of time in Vineyard waters. Standing in the darkness and assessing the wind, we decided to proceed with the trip, but delay our planned 5AM start by 45 minutes, when the first light of dawn would be breaking; none of us wanted to paddle tippy boats into waves we couldn’t see coming. John and Tucker quickly unloaded their identical 18-foot Surge touring kayaks and packed their gear; John also rigged an ingenious “masthead” light to a pole above his aft deck… it was Derby time, after all, and we wanted to be as visible as possible to any fishing boats speeding out of Edgartown Harbor.

With the faintest glow in the eastern sky, it was time to go; my colleagues slid into the cockpits of their sea kayaks and secured spray skirts around the coamings to keep any water out, while I lowered myself into the “bucket” of my hybrid surf ski– a sea kayak hull with sculpted seat-and-footwells in the deck for a “sit-on-top” rather than “sit-in” paddling posture. I’d added a custom foam backrest and inflatable seat pad to the bucket, since a paddler’s posterior is the first thing to complain when seated for hours on end, and we were looking at 33 miles– and at least six hours afloat– before taking our one planned break. That would be the furthest I’d ever paddled a kayak in one “sitting”, and I didn’t want to be undone by a distressed derriere. We crossed Eel Pond to the tip of the surrounding barrier beach, our official Start and Finish line; pointing our bows and headlamps to the northeast, I hit the GPS “START” button– and we were off!

Course Charted ,Martha’s Vinyard

THE IDEA OF KAYAKING AROUND THE VINEYARD in a single day had first occurred to me after racing the kayak component of the 2007 Vineyard Challenge, the legendary ‘round-the-island windsurf race founded by the equally legendary Nevin Sayre. While the kayak course was only 7 miles long, it got me thinking about what it would take to “go the distance” under paddle power– either individually or in relay format, with three or four kayakers per team. Although that year proved to be final running of the Vineyard Challenge, the idea of a one-day circumnavigation-by-paddle stuck with me. I began studying the nautical chart, measuring distances, calculating speeds, estimating times and– most critically– poring over the Eldridge Tide Book.

As all sailors know, Nantucket Sound is effectively a huge tidal pond which fills and drains through three main conduits: Vineyard Sound (between the north shore of the Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands), Muskeget Channel (between Chappaquiddick and Nantucket), and Great Round Shoal Channel (between Nantucket and Monomoy Island at the elbow of Cape Cod). As the tide rises in the Atlantic, it pours in through these three straits at 2-3 knots ( a knot being 1.15 miles per hour), and even higher velocities around points and headlands; once Nantucket Sound is full and the tide starts dropping in the Atlantic, the process reverses and all that water roars back out from whence it came. Six+ hours later, the cycle starts all over again. For kayakers, who generally paddle at speeds between 4 and 5 miles per hour, it is absolutely critical to time coastwise passages with favorable tidal currents, gaining a 2+ knot “push” whenever possible; conversely, one never wants to paddle against a foul current and make minimal forward progress despite herculean effort.

The Tide Book made it easy to circle the dates which offered the most favorable currents for a pre-dawn start; not nearly as predictable, of course, would be the wind direction and velocity on those dates, which would largely determine whether our route would go clockwise or counterclockwise. In either direction, by starting from Edgartown at high tide we’d have twelve hours to reach critical points– West Chop if clockwise, Wasque if counterclockwise– or otherwise face a debilitating foul current for the final eight miles of the trip. Although I’d been kayaking Vineyard waters for more than 30 years, for me the “wild card” of the route was the ocean leg along the island’s south shore– nearly 23 miles of open Atlantic between Gay Head and Wasque Point on Chappaquiddick, which I’d paddled for the first time just two weeks before. As the prevailing wind in summertime blows from the southwest, I had based most of my calculations and planning on a counterclockwise route to avoid the risk of headwinds in the Atlantic, and capitalize on the push of quartering afternoon tailwind and following seas by heading east in the ocean from Squibnocket to Wasque.

Tucker, Dana, John

BUT SEPTEMBER 22nd WAS ALSO THE FIRST DAY OF FALL, and lo and behold the forecast called for a moderate north wind at dawn, diminishing to practically nothing by noon before shifting to light southwest. We felt safe tackling the ocean leg first, so opted for the clockwise route instead. This offered several advantages: it would get the longer, riskier segment over with at the outset, when we had the most energy; provide a convenient lunch break (hopefully) during the noon hour; and, if we could maintain the intended pace, give us dreamlike conditions for the afternoon paddle up Vineyard Sound.

Our first leg would prove the most challenging of the whole trip, 4 miles into headseas over the port bow as dawn broke– but in truth we’d all seen far worse in distance training workouts. The wind was definitely letting up, and to my relief we encountered no powerboats as we crossed the outer harbor channel to Cape Poge Elbow. Once there, we skirted the shore to Cape Poge proper, then turned 90 degrees to starboard… and straight into sea kayaker’s heaven. The northerly tailwind and moderate following seas provided a “surfing” push, while beneath us the current was ebbing down Muskeget Channel at it’s peak, adding 2 knots to our speed for the entire length of East Beach. We now had company, with numerous fishing boats to our left, and determined surfcasters on the shore to our right. There was quite a crowd as we neared Wasque Point, but mercifully no treacherous rip at the corner since the tide and wind were working in concert. I suspect that our top GPS speed for the entire trip– 9.5 mph– was recorded as we zipped around the Point and into the Atlantic proper.

The ocean there was calm as the proverbial millpond, save for the rips and standing waves on the shoals outside the Norton Point breach. We gave those a wide berth, then skirted the shore to South Beach off Katama, where we rafted up for a break and reviewed our strategy. It was overcast and misty, with perhaps five miles visibility; we stood no chance of seeing our objective– the high ground of Chilmark and Squibnocket Point 15 miles distant– but the wind was now so light and the seas so benign that we decided to follow the straight GPS line rather than hug the coast. In so doing we’d be paddling a shorter distance, but also end up 2-1/2 miles out to sea at the furthest point; if wind and wave conditions worsened, or fog rolled in, things might get dicey… but, feeling safety in numbers, we set up a “train” with one boat leading and the other two tucked in right behind (similar to a draft pack in cycling)… and headed west/southwest towards the blank, murky horizon.

THE SOUTH SHORE OF THE VINEYARD, when viewed from the ocean, presents a long, low, unbroken strand of beach with a featureless backdrop of scrub oak woods. In actuality behind that beach lie fifteen coastal ponds– some Great, some not– and expansive tracts of sandplain grassland; but from offshore it all looks the same. Two weeks earlier I’d covered this course in reverse– starting from Menemsha, marking the GPS waypoints for the Gay Head Cliffs and Squibnocket Point, then paddling east the length of the south shore and ducking in through the Norton Point breach to finish. There were sizable swells from Hurricane Leslie that day, so I’d stayed well offshore to avoid any breakers on shoals. East of Squibnocket were the recognizable landmarks: Stonewall Beach and bluffs, the lofty heights of Wequobsque Cliffs, Lucy Vincent Beach, Abel’s Hill above Chilmark Pond, and then…. nothing: just flat white beach stretching east as far as the eye could see, with a low strip of trees above it. That landscape seemed to go on endlessly, with the furthest point forever receding to the distance, until at last the Edgartown water tower and Katama Farm silos peeked above the horizon; eventually the crowd of sunbathers on South Beach signaled that the end was near.

There were no beach crowds this morning, though– just gray mist and a calm sea. I reassured my fellow paddlers that we would indeed find land up ahead, as the shoreline to our right slid further away. We never saw the most prominent landmark– the 80-foot Wequobsque Cliffs (also known as Windy Gates)– as they were draped in fog the whole time. As we progressed further west, we began to feel the lift of sizable ocean swells which I knew would be welcomed by the surfers in Squibnocket Bight, up ahead to our right. … then it began to clear, and the cliffs of Squibnocket Point came into view dead ahead. We drew close just as summer turned officially to fall at 10:49AM… the long haul was almost over, and I knew that the scenery would soon improve in the most dramatic fashion!

Swell

We passed Squibnocket on surfable swells, then tucked in close to the beach, amazed by the size and sculptural quality of the dunes along the Moshup Trail shore. Five miles ahead rose the dramatic southwest rampart of the Gay Head Cliffs; I looked at my watch, and began crunching numbers. It was just past 11:00; the low tide had gone slack off the Cliffs an hour earlier, and was now beginning to flood northeast into Vineyard Sound– perfect. That current would remain favorable for at least five hours, by which time I hoped we’d be past the final headland of the route, East Chop. The clock was ticking.

Dana approaching Gays Head

Cliffs

No matter the timeline, though– one cannot hurry past the Gay Head (Aquinnah) Cliffs in a kayak…. the scenery is so spectacular, the setting so unique, the scale so overwhelming, that the paddler simply must stop, look up, and marvel. That we did, drifting along and taking photos, as the current swept past boulders crowded with gulls and cormorants. There is likely no other East Coast escarpment south of Acadia as dramatic as Gay Head– and certainly none more majestic and colorful when viewed from just offshore.

John

Rounding the corner, we beelined for the next waypoint– Dogfish Bar, the expansive beach along Lobsterville Road. This was our lunch spot, where we made landfall at 12:20 PM, with almost 33 miles tallied on the GPS odometer… and 22 left to go. The “wild card” ocean leg was behind us; I was happy to be back in familiar waters. It was a treat to stand up, stretch, walk about a bit, and enjoy a relaxed lunch in an idyllic setting. It was overcast when we landed, but during lunch the clouds began to dissipate, the sun broke through, and the sky turned a brilliant blue. After making cell calls to update friends on our progress, we reboarded and set off at 1:00 PM in glorious early fall sunshine, and the lightest of southwest breezes.

Mile 33 Lunch Time

OUR LINE WOULD TAKE US STRAIGHT TO CEDAR TREE NECK, the furthest point visible– and 8 miles distant– keeping us well offshore of Menemsha. While it would have been more scenic to paddle right along the coast, that would have added more than a mile to our total distance, taken us out of the most advantageous currents and put us behind the tide schedule. Regardless, we still enjoyed a beautiful view of the Vineyard’s north shore, which is strikingly different from the low, flat sameness of the Atlantic side: wooded morainal hills, prominent bluffs, and boulder-strewn headlands with white sand beaches in between. Most dramatic of all were the sheer sand cliffs of Menemsha Hills Reservation, with the remnant chimney of the brickworks ruins rising from the Roaring Brook hollow just beyond. Then came Spring Point, Cape Higgon, and the pristine shoreline of Seven Gates Farm; this is a side of the Vineyard that non-boaters never get to see, and my friends were amazed by the rural quality of the landscape.

Equally amazing were the speeds I was seeing on the GPS: often over 7mph– and sometimes even 8– as we rode the tidal river northeast towards West Chop. While the southwest tailwind was too light to provide any additional push, the lobster pot buoys dragged under by the current left no doubt as to the flood tide’s beneficial effect. I’d rounded Cedar Tree Neck many times before, almost always encountering standing waves or some odd tidal vortex…. but today the rip was minimal; we zipped by no problem as the steep sand face of Makonikey Head came into view. As we passed Pauls Point– the western end of the Lamberts Cove bight– a powerboat bore down on us from the north, captained by a friend of John’s from the Cape, with John’s wife Fran and a crowd of spectators aboard. We took a floating break, photographed back-and-forth, and marveled at how perfect the weather conditions had become. After ten or fifteen minutes we resumed paddling, with a second rendezvous planned off Oak Bluffs. The current had abated markedly off Lamberts Cove, and I knew we’d seen the best of it– but the tide was still in our favor, and once past Makonikey we’d have a straight 3.4 mile shot to West Chop…. just two more right-hand turns, and we’d be in the home stretch!

At the peak of the flood, the incoming tide rips past West Chop at 3-1/2 knots, or 4 statute miles per hour. We had missed that peak by two hours, but still enjoyed a 2-knot push rounding the island’s northernmost point, while also transitioning from Vineyard into Nantucket Sound. Seas were lumpy– as they almost always are at this juncture– but still we stopped and drifted long enough to photograph the lighthouse and celebrate another milestone of the trip… then it was on to East Chop. While only 2.2 miles across, the stretch between the Chops is always rough in the afternoon given the confluence of wind, current and boat wakes– but once again we were fortunate to encounter nothing really challenging. We were definitely slowing down, yet closer to home with every stroke.

Mile 42

THE GREEN CAN OFF EAST CHOP stood straight up in the water as we passed– a sure sign that the flood tide had gone slack, and was just about to turn against us. Luckily, the currents are weak at the beginning of each cycle, so I knew we’d beat out the worst of the ebb. Rounding the corner (our last right-hand turn!), the Oak Bluffs Steamship Wharf came into view– and beyond it in the far distance, white blocks against a green backdrop signified the stately houses overlooking Eel Pond; the end was now in sight!

We passed the Oak Bluffs Harbor jetties as John’s friends in the powerboat came out to escort us the rest of the way, then weaved between the pilings of the Steamship Pier. From scores of training workouts I knew that the straight line to our finish from here was exactly 4.7 miles; while fish pot buoys indicated the faintest hint of current against us, the wind was still mercifully light. I had worried that the normally brisk afternoon southwest wind, blowing smack on our starboard beam (90 degrees from the right) might make for a lot of extra work, and possibly force us to hug the shore for shelter– but today’s benign breeze was a non-issue as we paddled the offshore line, side-by-side past familiar landmarks in the arc of State Beach: Farm Pond jetties, Harthaven jetties, Little Bridge, Big Bridge, and the lifeguard stand at Bend-in-the-Road. I tried not to look at my watch or the GPS, but knew we were closing in on 11 hours paddling time– could we beat it? We pushed the pace a little bit, but this was never meant to be a race; from the get-go, we had treated it more as an expedition. After crossing the shoals outside Eel Pond, I paddled my bow right onto the tip of the barrier beach and hit “STOP”. Dismounting and standing up exultantly, my left leg immediately cramped and I keeled over face first into the shallows– finished, in every sense of the word!

It was just past 5:30 on a warm, sparkling, first-day-of-Fall evening…. we had set out past this very same point nearly twelve hours earlier into darkness, bumpy headseas, and a brisk northerly wind; conditions had done nothing but improve ever since. Subtracting the 40-minute lunch break, our GPS-verified paddling time was 11 hours and 4 minutes; our average speed for the entire trip 5.0mph (true paddling speed was no doubt a little faster, since we took five or six floating photographic breaks); maximum speed 9.5 mph; and total distance exactly 55.0 statute miles. John bid his wife and friends adieu, and we paddled happily across Eel Pond to the town landing. Despite my displeasure and skepticism at what I’d seen upon arrival at 4:30 that morning, the day had turned out to be perfect; indeed, it’s extremely rare for conditions to remain as placid as they did for such a long a time and distance– the weather gods had proven benevolent after all! The END!

Dana and Tucker at Finish!

Mission Accomplished, Dana,Tucker,John

Addenda: While ours is the fastest single day circumnavigation-by-paddle that I know of, it was not the first; David Duarte (then of Aquinnah, now of VH) paddled his folding kayak clockwise, starting and finishing at Dogfish Bar, in an unrecorded amount of time at an uncertain date in the 1990s.

Planning the trip involved careful calculations relative to the current diagrams in the Tide Book; the best days were those with a high tide off Edgartown at 5AM– our intended start time. The currents would thereafter be equally favorable for either a clockwise or counterclockwise course, with time limits in each direction: if clockwise, we would have to reach West Chop in 12 hours or face a foul current the rest of the way; conversely, if going counterclockwise we would have to reach Wasque Point by 5PM or end up paddling on a treadmill after 45 miles. The currents on September 22nd behaved exactly as predicted.

As far as training went, we all raced the 20 mile Blackburn Challenge around Cape Ann in mid-July, and thereafter did most of our long sessions individually, save for a final 30+ mile workout John and Tucker paddled together along the north shore of MA in early Sept. I used my long workouts to mark the waypoints, paddling from Menemsha to Edgartown in early July, around Chappaquiddick in late August, and the long Atlantic leg from Menemsha around Gay Head and Squibnocket, then east to the Norton Point breach in early September. None of us did anything close to 55 miles in a single outing, but by planning the rest stop at Dogfish Bar we were confident we could make the distance.

While I didn’t work it into the text, we did have one mishap early on, when Tucker capsized off East Beach, Chappy (for reasons still undetermined, maybe not enough coffee?)…. while it turned out to be a non-issue (other than the 15 minutes it took to re-board, pump out and regroup), it certainly did shake my confidence (ie, would there be more capsizes throughout the day?) Tucker has no qualms about that incident being woven into the story, if there’s room or interest; I’m confident I could inject a degree of humor, which is by and large lacking otherwise. It would fit well into the top paragraph of the third page; “We now had company”… could become” We now had an audience”…. and proceed from there!

Republished with Permission from Atlantic Coastal Kayaker in shorten version.

Tamsin Venn, Publisher

Atlantic Coastal Kayaker

224 Argilla Road

Ipswich, Massachusetts 01938

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.